|

Posted: 8/6/2015 11:23:39 PM EDT

On the 70th anniversary of the first use of A-bombs in war, I'd like to look a bit beyond the actual atomic missions. To get to the point where the US was able to send the 509th out in August of 1945, three major things had to happen, all of which were extremely costly in blood and treasure. First, we needed "the bomb"- which story is best covered in a review of the Manhattan Project. Second, we needed the long range bomber to drop the A-bombs, and indeed the story of the development of the B-29,(and its backup plan- the B-32) is worth a look. Finally, we needed a place from which it was possible to launch the bombing missions. The AAF originally tried to launch B-29 missions from the CBI, but the logistics problems there were insurmountable. We needed to get to the Mariana Islands, and this thread will be a brief review of the overall plan to get to those islands.

Japanese reach at its maximum in 1942:

From the US Army history book American Military History, Chapter 23- World War II: The War Against Japan:

"Meanwhile, in the spring and summer of 1943, a strategy for the defeat of Japan began to take shape within Allied councils. The major Allied objective was control of the South China Sea and a foothold on the coast of China, so as to sever Japanese lines of communications southward and to establish bases from which Japan could first be subjected to intensive aerial bombardment and naval blockade and then, if necessary, invaded. The first plans for attaining this objective envisioned Allied drives from several different directions- by American forces across the Pacific along two lines, from the South and Southwest toward the Philippines and from Hawaii across the Central Pacific; and by British and Chinese forces along two other lines, the first a land line through Burma and China and the second a sea line from India via the Netherlands Indies, Singapore, and the Strait of Malacca into the South China Sea. Within the framework of this tentative long-range plan, the U.S. Joint Chiefs fitted their existing plans for completion of the campaign against Rabaul, and a subsequent advance to the Philippines, and developed a plan for the second drive across the Central Pacific. They also, in 1942 and 1943, pressed the Chinese and British to get a drive under way in Burma to reopen the supply line to China in phase with their Pacific advances, offering extensive air and logistical support.

...

Prospects of an advance through China to the coast faded rapidly in 1943. At the Casablanca Conference in January the Combined Chiefs agreed on an ambitious operation, called ANAKIM, to be launched in the fall of 1943 to retake Burma and reopen the supply line to China. ANAKIM was to include a British amphibious assault on Rangoon and an offensive into central Burma, plus an American-sponsored Chinese offensive in the north involving convergence of forces operating from China and India. ANAKIM proved too ambitious; even limited offensives in Southeast Asia were postponed time and again for lack of adequate resources. By late 1943 the Americans had concluded that their Pacific forces would reach the China coast before either British or Chinese forces could come in through the back door. At the SEXTANT Conference late in 1943 the Combined Chiefs agreed that the main effort against Japan should be concentrated in the Pacific along two lines of advance, with operations in the North Pacific, China, and Southeast Asia to be assigned subsidiary roles.

In this strategy the two lines of advance in the Pacific -the one across the Central Pacific via the Gilberts, Marshalls, Marianas, Carolines, and Palaus toward the Philippines or Formosa (Taiwan) and the other in the Southwest Pacific via the north coast of New Guinea to the Vogelkop and thence to the southern Philippines-were viewed as mutually supporting. (Map 44) Although the Joint Chiefs several times indicated a measure of preference for the Central Pacific as the area of main effort, they never established any real priority between the two lines, seeking instead to retain a flexibility that would permit striking blows along either line as opportunity offered. The Central Pacific route promised to force a naval showdown with the Japanese and, once the Marianas were secured, to provide bases from which the U.S. Army Air Forces' new B-29 bombers could strike the Japanese home islands. The Southwest Pacific route was shorter, if existing bases were taken into consideration, and offered more opportunity to employ land-based air power to full advantage. The target area for both drives, in the strategy approved at SEXTANT, was to be the Luzon-Formosa-China coast area. Within this area the natural goal of the Southwest Pacific drive was the Philippines, but that of the Central Pacific drive could be either the Philippines or Formosa. As the drives along the two lines got under way in earnest in 1944, the choice between the two became the central strategic issue."

http://www.history.army.mil/books/AMH/AMH-23.htm

Good map, even though in French. Yellow highlighted areas are Japanese strongpoints that were bypassed:

"The Joint Chiefs, quickly seizing the fruits of their strategy of opportunism, on March 12, 1944, rearranged the schedule of major Pacific operations. They provided for the assault by MacArthur's forces on Hollandia and Aitape in April with the support of a carrier task force from the Pacific Fleet, to be followed by Nimitz's move into the Marianas in June and into the Palaus in September. While Nimitz was employing the major units of the Pacific Fleet in these ventures, MacArthur was to continue his advance along the New Guinea coast with the forces at his disposal. In November, he was again to have the support of main units of the Pacific Fleet in an assault on Mindanao. Refusing yet to make a positive choice of what was to follow, the Joint Chiefs directed MacArthur to plan for the invasion of Luzon and Nimitz to plan for the invasion of Formosa early in 1945.

"The Joint Chiefs, quickly seizing the fruits of their strategy of opportunism, on March 12, 1944, rearranged the schedule of major Pacific operations. They provided for the assault by MacArthur's forces on Hollandia and Aitape in April with the support of a carrier task force from the Pacific Fleet, to be followed by Nimitz's move into the Marianas in June and into the Palaus in September. While Nimitz was employing the major units of the Pacific Fleet in these ventures, MacArthur was to continue his advance along the New Guinea coast with the forces at his disposal. In November, he was again to have the support of main units of the Pacific Fleet in an assault on Mindanao. Refusing yet to make a positive choice of what was to follow, the Joint Chiefs directed MacArthur to plan for the invasion of Luzon and Nimitz to plan for the invasion of Formosa early in 1945.

The March 12 directive served as a blueprint for an accelerated drive in the Pacific in the spring and summer of 1944. On April 22 Army forces under MacArthur landed at Hollandia and Aitape. At neither place was the issue ever in doubt, although during July the Japanese who had been bypassed at Wewak launched an abortive counterattack against Aitape. Protected by land-based aircraft from Hollandia, MacArthur's Army units next jumped 125 miles northwest on May 17 to seize another air base site at Wakde Island, landing first on the New Guinea mainland opposite the chief objective. A ground campaign of about a month and a half ensued against a Japanese division on the mainland, but, without waiting for the outcome of the fight, other Army troops carried the advance northwestward on May 27 another 180 miles to Biak Island.

As this point the wisdom of conducting twin drives across the Pacific emerged. The Japanese Navy was preparing for a showdown battle it expected to develop off the Marianas in June. MacArthur's move to Biak put land-based planes in position to keep under surveillance and to harry the Japanese Fleet, which was assembling in Philippine waters before moving into the Central Pacific. Reckoning an American-controlled Biak an unacceptable threat to their flank, the Japanese risked major elements of their fleet to send strong reinforcements to Biak in an attempt to drive MacArthur's forces ok the island. They also deployed to bases within range of Biak about half their land-based air strength from the Marianas, Carolines, and Palaus?planes upon which their fleet depended for support during the forthcoming battle off the Marianas.

After two partially successful attempts to reinforce Biak, the Japanese assembled for a third try enough naval strength to overwhelm local American naval units; but just as the formidable force was moving toward Biak the Japanese learned the U.S. Pacific Fleet was off the Marianas. They hastily assembled their naval forces and sailed northwestward for the engagement known as the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Having lost their chance to surprise the U.S. Navy, handicapped by belated deployment, and deprived of anticipated land-based air support, the Japanese suffered another shattering naval defeat. This defeat, which assured the success of the invasions of both Biak and the Marianas, illustrates well the interdependence of operations in the two Pacific areas. It also again demonstrated that the U.S. Pacific Fleet's carrier task forces were the decisive element in the Pacific war.

Army and Marine divisions under Nimitz landed on Saipan in the Marianas on June 15, 1944, to begin a bloody three-week battle for control of the island. Next, on July 21, Army and Marine units invaded Guam, 100 miles south of Saipan, and three days later marines moved on to Tinian Island. An important turning point of the Pacific war, the American seizure of the Marianas brought the Japanese home islands within reach of the U.S. Army Air Forces' B-29 bombers, which in late November began to fly missions against the Japanese homeland."

US advances in the Pacific:

And, the results of the Central Pacific drive, all easily resupplied with bombs and fuel by the Navy.....

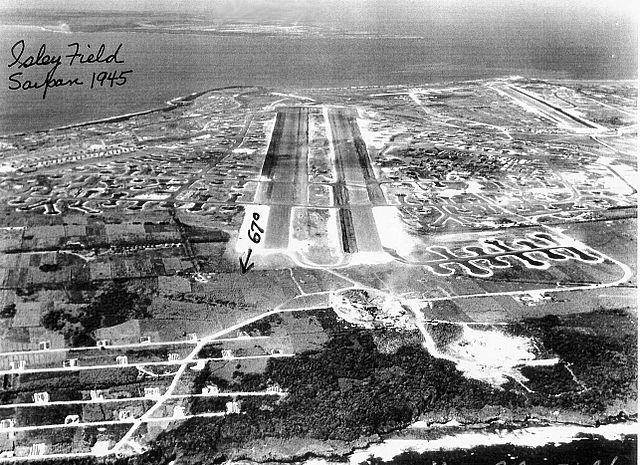

Isley Field, Saipan:

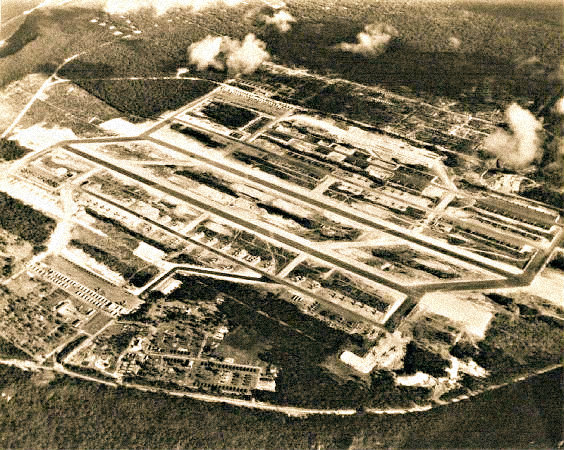

Tinian:

Tinian:

Northwest Field, Guam:

Northwest Field, Guam:

|

Win a FREE Membership!

Win a FREE Membership!